I've always been interested in how knowledge from one field can enrich another. Having worked in both architectural design and software development, I've observed a number of parallels between these seemingly disparate worlds. In a previous article, I looked at what urban designers could learn from the medical profession, and in this one I'm looking at what software managers could learn from (building) architects.

The three axes of architectural temperament

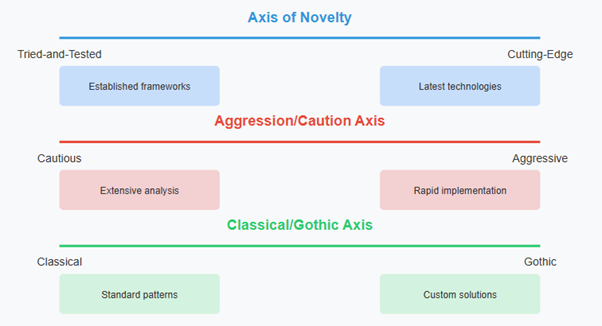

Through my experience in both fields, I've noticed that architects - whether designing buildings or software systems - tend to position themselves somewhere along three distinct axes:

The axis of novelty

This axis is straightforward to describe. At one end are architects who embrace cutting-edge trends. In buildings, they incorporate the latest materials, styles, fashions, and theories of spatial arrangement. In software, they eagerly adopt new technologies, languages, and frameworks - sometimes before the business case fully justifies it.

At the opposite end are architects who rely on proven approaches. These professionals prefer established technologies and methodologies with predictable outcomes, prioritizing reliability over innovation.

The aggression/caution axis

Cautious architects will observe extensively before acting. They analyze existing structures - whether codebases or cityscapes - and contemplate multiple approaches before making decisions. They move deliberately, weighing potential consequences carefully.

Aggressive architects attack problems immediately. In software, they produce hundreds of lines of code before pausing to evaluate. Their counterparts in building architecture quickly propose demolitions and bold new structures, eager to make their mark.

The classical/gothic axis

This axis is more nuanced and requires a more detailed explanation.

Classical architects follow established conventions and patterns. In building architecture, this means drawing inspiration from historical patterns such as Greek and Roman styles, prioritizing symmetry, order, precedent and external appearance, sometimes at the expense of interior functionality. In software, classical architects embrace standard frameworks, component libraries, and design patterns that other software developers will readily recognize.

Gothic architects express the unique requirements of each project. In buildings, this means celebrating individual craftsmanship from the overall structure down to small details, with form following function. In the software world, Gothic architects prefer custom solutions, often writing code from scratch and inventing their own methods rather than using external libraries. Their work precisely addresses requirements but often sacrifices legibility and maintainability because it takes time for others to understand what they have done.

Implications for software development managers

Understanding where your team members fall on these axes provides valuable insight for managing software development effectively.

Managing the novelty spectrum

While extremes at either end (outdated technologies or untested novelties) should be avoided, most positions along the middle 95% of this axis work well. A healthy team often benefits from a mix - some members who stay current with emerging technologies and others who ensure stability with established approaches.

Balancing aggression and caution

The most effective developers typically occupy the middle ground on this axis. Extreme aggression can lead to technical debt and unstable systems, while excessive caution might result in analysis paralysis and missed deadlines.

"Courage" remains one of the five core values of Extreme Programming (XP) for good reason - progress requires boldness. However, caution becomes essential when working with complex or brittle systems. Managers should help team members develop situational awareness about when to move quickly versus when to proceed with care.

Navigating classical vs gothic approaches

For most enterprise software projects, developers should lean toward the classical end of this spectrum. Code legibility and maintainability are crucial when multiple developers work on the same codebase over time. Standardized patterns and frameworks enhance team efficiency and knowledge transfer, and make it easier to onboard new team members. In the long term, a classical approach saves a lot of time and money.

However, there are two possible exceptions to this - when creating something entirely new where no established patterns or precedents exist, Gothic architects can help teams move quickly, establish new standards, and explore uncharted territory. Secondly, on solo projects when a single developer maintains the entire codebase, Gothic approaches may allow for precise adaptation to requirements without the need to communicate with other team members.

Practical applications

As a software development manager, consider these strategies:

- Team composition: Assemble teams with complementary positions along these axes. A team of only aggressive innovators might create exciting but unstable systems, while a team of cautious classicists might move too slowly for business needs.

- Project matching: Assign developers to projects that align with their architectural temperaments. Your gothic innovators might excel at prototyping new concepts, while your classical stabilizers can transform those prototypes into production-ready systems.

- Professional development: Help team members recognize their natural positions on these axes and encourage professional development which expands their range, increasing their versatility and value to the organization.

- Communication frameworks: Establish vocabulary and processes that bridge differences between architectural approaches. When team members understand these axes, they can better articulate their decisions and understand others' perspectives.

Conclusion

The parallels between building architecture and software development offer valuable frameworks for understanding team dynamics. By recognizing where each team member falls on the axes of novelty, aggression/caution, and classical/gothic approaches, managers can build more balanced teams, make more effective assignments, and facilitate better communication.

The most successful software projects often emerge from teams that balance these different architectural temperaments - combining innovation with stability, boldness with deliberation, and standardization with customization to meet the unique needs of each project.

I'd be interested to hear from software managers whether this system makes sense to them, and how analysis of temperaments or personality types can be leveraged to create software solutions more effectively.

Contact us